| 68b. The Circular Flow of Man's Life within the World Of Sense, Soul And Spirit: The Essence of Sleep and Death

06 Apr 1908, Goteborg |

|---|

| 68b. The Circular Flow of Man's Life within the World Of Sense, Soul And Spirit: The Essence of Sleep and Death

06 Apr 1908, Goteborg |

|---|

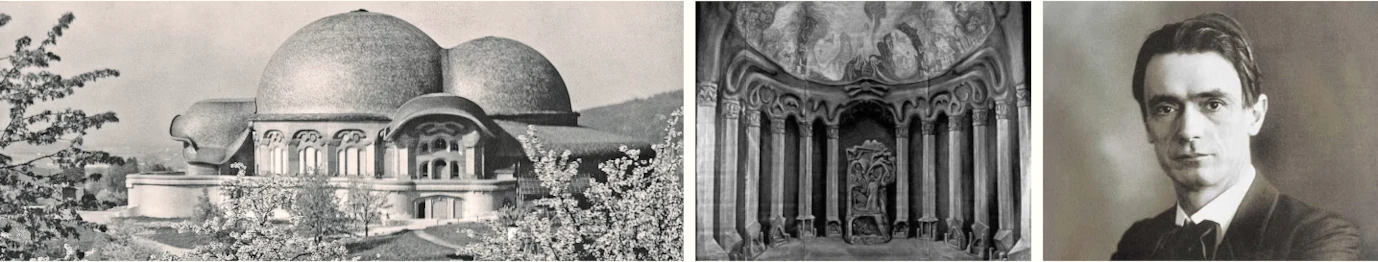

Report in “Göteborgs Aftonblad”, No. 81, April 7, 1908 “Theosophy – Goethe and Hegel” was the subject of a lecture by Dr. Rudolf Steiner, a German writer and lecturer and one of the leading German Theosophists, as well as a prominent Goethe expert, which was also mentioned during his introduction to a Swedish audience. As can be seen from the title, yesterday's lecture was a theosophical lecture, the purpose of which was to show that the worldviews of both Goethe and Hegel essentially corresponded to those of modern theosophy. With a flowing eloquence, sometimes driven by high-spirited pathos, the speaker developed his theories in a lecture that lasted almost an hour and a half, apparently holding the interest of the few spectators the whole time. Strangely, the audience in this otherwise quite Theosophically interested city consisted of just under 100 people. Perhaps it was the German language that deterred them – the universal Theosophical language is actually English – or perhaps it was the old Hegel, with whom probably the majority of today's audience has failed to become more closely acquainted. Goethe, on the other hand, we should all know – including his rather indigestible second part of “Faust”. However, it is from this part that Dr. Steiner draws his evidence that Goethe appears as one of the “initiates” - one of those who, through the power of higher intuition, can see a higher reality behind the physical world, an embodiment of ideas - and, in the theosophical sense, comes into contact with the divine spirit that permeates the universe. In particular, the speaker tried to show that Goethe paid homage to the theosophical doctrine of reincarnation. The speaker emphasized that in order to understand the second part of “Faust”, it must be studied in the theosophical light. That “the universal Goethe” and in particular his Faust poem, the subject of seventy times seven interpreters, was thus also exploited for the theosophical exegesis, is hardly more than one might expect. This part of the lecture was undoubtedly the most interesting. The speaker's attempt to turn the pantheist Hegel, with his idea of the individual as a transitory momentum, into a theosophical adept seemed less successful. Finally, the speaker returned to the Faust poet and ended with these his words, which, like so much else of what “the great pagan” said, bear wonderful witness to his belief in the divine in man:

|