| 304. Waldorf Education and Anthroposophy I: The Fundamentals of Waldorf Education

11 Nov 1921, Aarau Translated by René M. Querido |

|---|

| 304. Waldorf Education and Anthroposophy I: The Fundamentals of Waldorf Education

11 Nov 1921, Aarau Translated by René M. Querido |

|---|

QUESTIONER: RUDOLF STEINER: During my life, which by now can no longer be described as short, I have tried to follow up various life situations related to this question. On one hand, I have really experienced what it means to hear, in one’s childhood, a great deal of talk about a highly esteemed and respected relative whom one had not yet met in person. I have known what it is to become thoroughly familiar with the reverence toward such a person that is shared by all members of the household, by one’s parents as well as by others connected with one’s upbringing. I have experienced what it means to be led for the first time to the room of such a person, to hold the door handle in my hand, feeling full of awe and reverence. To have undergone such an experience is of lasting importance for the whole of one’s life. There can be no genuine feeling for freedom, consistent with human dignity, that does not have its roots in the experience of reverence and veneration such as one can feel deeply in one’s childhood days. On the other hand, I have also witnessed something rather different. In Berlin, I made the acquaintance of a well-known woman socialist, who often made public speeches. One day I read, in an otherwise quite respectable newspaper, an article of hers entitled, “The Revolution of our Children.” In it, in true socialist style, she developed the theme of how, after the older generation had fought—or at least talked about—the revolution, it was now the children’s turn to act. It was not even clear whether children of preschool age were to be included in that revolution. This is a different example of how the question of authority has been dealt with during the last decades. As a third example, I would like to quote a proposal, made in all seriousness by an educationalist who recommended that a special book be kept at school in which at the end of each week—it may have been at the end of each month—the pupils were to enter what they thought about their teachers. The idea behind this proposal was to prepare them for a time in the near future when teachers would no longer give report “marks” to their pupils but pupils would give grades to their teachers. None of these examples can be judged rightly unless they are seen against the background of life as a whole. This will perhaps appear paradoxical to you, but I do believe that this whole question can be answered only within a wider context. As a consequence of our otherwise magnificent scientific and technical culture—which, in keeping with its own character, is bound to foster the intellect—the human soul has gradually become less and less permeated by living spirit. Today, when people imagine what the spirit is like, they usually reach only concepts and ideas about it. Those are only mental images of something vaguely spiritual. This, at any rate, is how the most influential philosophers of our time speak about the spiritual worlds as they elaborate their conceptual theories of education. This “conceptuality” is, of course, the very thing that anthroposophical spiritual science seeks to overcome. Spiritual science does not want its adherents merely to talk about the spirit or to bring it down into concepts and ideas; it wants human beings to imbue themselves with living spirit. If this actually happens to people, they very soon begin to realize that we have gradually lost touch with the living spirit. They recognize that it is essential that we find our way back to the living spirit. So-called intellectually enlightened people in particular have lost the inner experience of living spirit. At best, they turn into agnostics, who maintain that natural science can reach only a certain level of knowledge and that that level represents the ultimate limit of what can in fact be known. The fact that the real struggle for knowledge only begins at this point, and that it leads to a living experience of the spiritual world—of this, generally speaking, our educated society has very little awareness. And what was the result, or rather what was the cause, of our having lost the spirit in our spoken words? Today, you will find that what you read in innumerable articles and books basically consists of words spilling more or less automatically from the human soul. If one is open-minded and conversant with the current situation, one often needs to read no more than the first few lines or pages of an article or book in order to know what the author is thinking about the various points in question. The rest follows almost automatically out of the words themselves. Once the spirit has gone out of life, the result is an empty phrase-bound, cliché-ridden language, and this is what so often happens in today’s cultural life. When people speak about cultural or spiritual matters or when they wish to participate in the cultural spiritual sphere of life, it is often no longer the living spirit that speaks through their being. It is clichés that dominate their language. This is true not only of how individuals express themselves. We find it above all in our “glorious” state education. Only think for a moment of how little of real substance is to be found in one or another political party that offers the most persuasive slogans or “party-phrases.” People become intoxicated by these clichés. Slogans might to some degree satisfy the intellect, but party phrases will not grasp real life. And so it must be said that what we find when we reach the heights of agnosticism—which has already penetrated deeply into our society—is richly saturated with empty phrases. Living so closely with such clichés, we no longer feel a need for what is truly living in language. Words no longer rise from profound enough depths of the human soul. Change will occur only if we permeate ourselves with the spirit once more. Two weeks ago, I wrote an article for The Goetheanum under the heading, “Spiritual Life Is Buried Alive.” In it, I drew attention to the sublime quality of the writing that can still be found among authors who wrote around the middle of the nineteenth century. Only very few people are aware of this. I showed several people some of these books that looked as if they had been read almost continually for about a decade, after which they seemed to have been consigned to dust. Full of surprise, they asked me, “Where did you find those books?” I explained that I am in the habit, now and then, of poring over old books in second-hand bookshops. In those bookshops, I consult the appropriate catalogs and ask for certain chosen books to be delivered to wherever I am staying. In that way I manage to find totally forgotten books of all kinds, books that will never be reprinted but that give clear evidence of how the spirit has been “buried alive” in our times, at least to a certain extent. Natural science is protected from falling into such clichés simply because of its close ties to experimentation and observation. When making experiments, one is dealing with actual spiritual facts that have their place in the general ordering of natural laws. But, excepting science, we have been gradually sliding into a life heavily influenced by clichés and phrases, by-products of the overspecialization of the scientific, technological development of our times. Apart from many other unhappy circumstances of our age, it is to living in such a phrase-ridden, clichéd language that we must attribute the problem raised by the previous speaker. For a child’s relationship to an adult is an altogether imponderable one. The phrase might well flourish in adult conversations, and particularly so in party-political meetings, but if one speaks to children in mere phrases, clichés, they cannot make anything of them. And what happens when we speak in clichés—no matter whether the subject is religious, scientific, or unconventionally open-minded? The child’s soul does not receive the necessary sustenance, for empty phrases cannot offer proper nourishment to the soul. This, in turn, lets loose the lower instincts. You can see it happening in the social life of Eastern Europe, where, through Leninism and Trotskyism, an attempt was made to establish the rule of the phrase. This, of course, can never work creatively and in Soviet Russia, therefore, the worst instincts have risen from the lower regions. For the same reason, instincts have risen up and come to the fore in our own younger generation. Such instincts are not even unhealthy in every respect, but they show that the older generation has been unable to endow language with the necessary soul qualities. Basically, the problems presented by our young are consequences of problems within the adult world; at least when regarded in a certain light, they are parents’ problems. When meeting the young, we create all too easily an impression of being frightfully clever, making them feel frightfully stupid, whereas those who are able to learn from children are mostly the wisest people. If one does not approach the young with empty phrases, one meets them in a totally different way. The relationship between the younger generation and the adult world reflects our not having given it sufficient warmth of soul. This has contributed to their present character. That we must not blame everything that has gone wrong entirely on the younger generation becomes clearly evident, dear friends, by their response to what is being done for our young people in the Waldorf school, even during the short time of its existence. As you have seen already, Waldorf education is primarily a question of finding the right teachers. I must confess that whenever I come to Stuttgart to visit and assist in the guidance of the Waldorf school—which unfortunately happens only seldom—I ask the same question in each class, naturally within the appropriate context and avoiding any possible tedium, “Children, do you love your teachers?” You should hear and witness the enthusiasm with which they call out in chorus, “Yes!” This call to the teachers to engender love within their pupils is all part of the question of how the older generation should relate to the young. In this context, it seems appropriate to mention that we decided from the beginning to open a complete primary school, comprising all eight classes in order to cover the entire age range of an elementary school. And sometimes, when entering the school building, one could feel quite alarmed at the apparent lack of discipline, especially during break times. Those who jump to judgment too quickly said, “You see what a free Waldorf school is like! The pupils lose all sense of discipline.” What they did not realize was that the pupils who had come to us from other schools had been brought up under so-called “iron discipline.” Actually, they have already calmed down considerably but, when they first arrived under the influence of their previous “iron discipline,” they were real scamps. The only ones who were moderately well-behaved were the first graders who had come directly from their parental homes—and even then, this was not always the case. Nevertheless, whenever I visit the Waldorf school, I notice a distinct improvement in discipline. And now, after a little more than two years of existence, one can see a great change. Our pupils certainly won’t turn into “apple-polishers” but they know that, if something goes wrong, they can always approach their teachers and trust them to enter into the matter sympathetically. This makes the pupils ready to confide. They may be noisy and full of boisterous energy—they certainly are not inhibited—but they are changing, and what can be expected in matters of discipline is gradually evolving. What I called in my lecture a natural sense of authority is also steadily growing. For example, it is truly reassuring to hear the following report. A pupil entered the Waldorf school. He was already fourteen years old and was therefore placed into our top class. When he arrived, he was a thoroughly discontented boy who had lost all faith in his previous school. Obviously, a new school cannot offer a panacea to such a boy in the first few days. The Waldorf school must be viewed as a whole—if you were to cut a small piece from a painting, you could hardly give a sound judgment on the whole painting. There are people, for instance, who believe that they know all about the Waldorf school after having visited it for only one or two days. This is nonsense. One cannot become fully acquainted with the methods of anthroposophy merely by sampling a few of them. One must experience the spirit pervading the whole work. And so it was for the disgruntled boy who entered our school so late in the day. Naturally, what he encountered there during the first few days could hardly give him the inner peace and satisfaction for which he was hoping. After some time, however, he approached his history teacher, who had made a deep impression on him. The boy wanted to speak with this teacher, to whom he felt he could open his heart and tell of his troubles. This conversation brought about a complete change in the boy. Such a thing is only possible through the inner sense of authority of which I have spoken. These things become clear when this matter-of-fact authority has arisen by virtue of the quality of the teachers and their teaching. I don’t think that I am being premature in saying that the young people who are now passing through the Waldorf school are hardly likely to exhibit the spirit of non-cooperation with the older generation of which the previous speaker spoke. It is really up to the teachers to play their parts in directing the negative aspects of the “storm and stress” fermenting in our youth into the right channels. In the Waldorf school, we hold regular teacher meetings that differ substantially from those in other schools. During those meetings, each child is considered in turn and is discussed from a psychological point of view. All of us have learned a very great deal during these two years of practicing Waldorf pedagogy. This way of educating the young has truly grown into one organic whole. We would not have been able to found our Waldorf school if we had not been prepared to make certain compromises. Right at the beginning, I drafted a memorandum that was sent to the education authorities. In it, we pledged to bring our pupils in their ninth year up to the generally accepted standards of learning, thus enabling them to enter another school if they so desired. The same generally accepted levels of achievement were to be reached in their twelfth and again in their fourteenth year. But, regarding our methods of teaching, we requested full freedom for the intervening years. This does constitute a compromise, but one must work within the given situation. It gave us the possibility of putting into practice what we considered to be essential for a healthy and right way of teaching. As an example, consider the case of school reports. From my childhood reports I recall certain phrases, such as “almost praiseworthy,” “hardly satisfactory” and so on. But I never succeeded in discovering the wisdom behind my teachers’ distinction of a “hardly satisfactory” from an “almost satisfactory” mark. You must bear with me, but this is exactly how it was. In the Waldorf school, instead of such stereotyped phrases or numerical marks, we write reports in which teachers express in their own style how each pupil has fared during the year. Our reports do not contain abstract remarks that must seem like mere empty phrases to the child. For, if something makes no sense, it is a mere phrase. As each child gradually grows up into life, the teachers write in their school reports what each pupil needs to know about him- or herself. Each report thus contains its own individual message, representing a kind of biography of the pupil’s life at school during the previous school year. Furthermore, we end our reports with a little verse, specially composed for each child, epitomizing the year’s progress. Naturally, writing this kind of report demands a great deal of time. But the child receives a kind of mirror of itself. So far, I have not come across a single student who did not show genuine interest in his or her report, even if it contained some real home truths. Especially the aptly chosen verse at the end is something that can become of real educational value to the child. One must make use of all means possible to call forth in the children the feeling that their guides and educators have taken the task of writing these reports very seriously, and that they have done so not in a onesided manner, but from a direct and genuine interest in their charges. A great deal depends on our freeing ourselves from the cliché-ridden cultivation of the phrase so characteristic of our times, and on our showing the right kind of understanding for the younger generation. I am well aware that this is also connected with psychological predispositions of a more national character, and to gain mastery over these is an even more difficult task. It might surprise you to hear that in none of the various anthroposophical conferences that we have held during the past few months was there any lack of younger members. They were always there and I never minced my words when speaking to them. But they soon realized that I was not addressing them with clichés or empty phrases. Even if they heard something very different from what they had expected, they could feel that what I said came straight from the heart, as all words of real value do. During our last conference in Stuttgart in particular, a number of young persons representing the youth movement were again present and, after a conversation with them lasting some one-and-a-half or two hours, it was unanimously decided to actually found an anthroposophical youth group, and this despite the fact that young people do not usually value anything even vaguely connected with authority, for they believe that everything has to grow from within, out of themselves, a principle that they were certainly not prepared to abandon. What really matters is how the adults meet the young, how they approach them. From experience—many times confirmed—I can only point out that this whole question of the younger generation is often a question of the older generation. As such, it can perhaps be best answered by looking a little less at the younger generation and looking a little more deeply into ourselves. A PERSON FROM THE AUDIENCE: If I may say something to the first speaker, who asked for a book to explain why young people behave as they do, I say: Don’t read a book. To find an answer, read us young people! If you want to talk to the younger generation, you must approach them as living human beings. You must be ready to open yourself to them. Young people will then do the same and young and old will become clear about what each is looking for. QUESTIONER: RUDOLF STEINER: The question everywhere is how to regain the lost respect for authority in individual human beings that will enable you as teachers and educators to find the right relationship to the young. That it is generally correct to state that young people do not find the necessary conditions for such a respect and sense of authority in the older generation and that they find among its members an attitude of compromise is in itself, in my opinion, no evidence against what I have said. This striving for compromise can be found on a much wider scale even in world events, so that the question of how to regain respect for human authority and dignity could be extended to a worldwide level. I would like to add that—of course—I realize that there exist good and devoted teachers as described by the last speaker. But the pupils usually behave differently when taught by those good teachers. If one discriminates, one can observe that the young respond quite differently in their company. We must not let ourselves be led into an attitude of complaining and doubting by judgments that are too strongly colored by our own hypotheses, but must be clear that ultimately the way in which the younger generation behaves is, in general, conditioned by the older generation. My observations were not meant to imply that teachers were to be held solely responsible for the faults of the young. At this point, I feel rather tempted to point to how lack of respect for authority is revealed in its worst light when we look at some of the events of recent history. Only remember certain moments during the last, catastrophic war. There was a need to replace older, leading personalities. What kind of person was chosen? In France, Clemenceau, in Germany, Hertling—all old men of the most ancient kind who carried a certain authority only because they had once been important personalities. But they were no longer the kind of person who could take his or her stance from a direct grasp of the then current situation. And what is happening now? Only recently the prime ministers of three leading countries found their positions seriously jeopardized. Yet all three are still in office, simply because no other candidate could be found who carried sufficient weight of authority! That was the only reason for their survival as prime ministers. And so we find that, in important world happenings, too, a general sense of authority has been undermined, even in leading figures. You can hardly blame the younger generation for that! But these symptoms have a shattering effect on the young who witness them. We really have to tackle this whole question at a deeper level and, above all, in a more positive light. We must be clear that, instead of complaining about the ways in which the young confront their elders, we should be thinking of how we can improve our own attitude toward young. To continue telling them how wrong they are and that it is no longer possible to cooperate with them can never lead to progress. In order to work toward a more fruitful future, we must look for what the spiritual cultural sphere, and life in general, can offer to help us regain respect and trust in the older generation. Those who know the young know that they are only too happy when they can have faith in their elders again. This is really true. Their skepticism ceases as soon as they can find something of real value, something in which they can believe. Generally speaking, we cannot yet say that life is ruled by what is right. But, if we offer our youth something true, they will feel attracted to it. If we no longer believe this to be the case, if all that we do is moan and groan about youth’s failings, then we shall achieve nothing at all. |

| 297. The Idea and Practice of Waldorf Education: Community From the Point of View of Spiritual Science

21 May 1920, Aarau |

|---|

| 297. The Idea and Practice of Waldorf Education: Community From the Point of View of Spiritual Science

21 May 1920, Aarau |

|---|

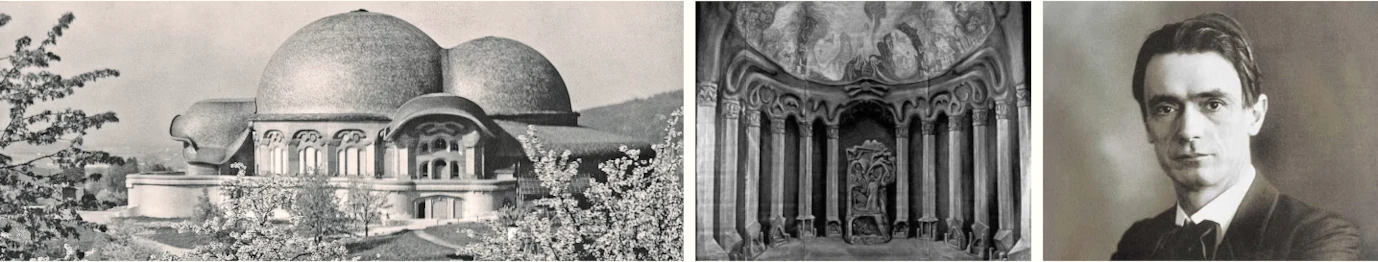

Great Questions of Humanity 1 are on the doorstep. The spiritual scientific direction, outwardly represented by the well-known building in Dornach, seeks to provide an answer to this. I will speak here of the pedagogical and social consequences that arise from this anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. Before I do that, I would like to give a broad outline of the nature of the whole spiritual-scientific direction. This is not about something that is sought outside of the human being, that could be demonstrated to humanity through experiments, but rather about the most inner human being, which hopes to be able to be implemented in the most practical way. Spiritual science does not want to overthrow the foundations of all previous world views, but rather to add something new to them: the view of a real spiritual life beyond the scientific experience, the realization of the spiritual nature of man. For three to four centuries, the basic ideas of scientific thinking have dominated our views. Spiritual science is not opposed to these. It recognizes the great triumphs of the scientific world view, but aims to be more scientific than the latter itself. It does not want to back down from the so-called limits of human knowledge, but to arrive at the true knowledge of man. If it has been said that where supernaturalism begins, science ends, then spiritual science also aims to work scientifically in this field. In order to reach this goal, it must first adopt the standpoint of intellectual modesty. A comparison: if you give a five-year-old child a volume of lyrical poems, he will play with it, tear it up, and after ten to twelve years he will be able to use the volume in a meaningful way. We must believe in these dormant developmental possibilities in the five-year-old child. The spiritual researcher now says that what lies within us is not limited to what has been formed by birth, inheritance and ordinary education. The forces of human nature are capable of development beyond that. Through intimate inner soul work, a person gradually learns to draw abilities from the depths of the soul, of which one has no inkling in ordinary life and [in ordinary] science. The principle here is that the person must methodically and constantly repeat the inner experiment, that he must persistently make an easily visible thought the guiding star of his consciousness. This self-made thought content is placed at the center of his consciousness, and he muster all his soul forces to set nothing but this thought content as his goal. The basis for this is intellectual modesty and belief in the possibility of development. After such an exercise in patience, we experience that human experience breaks away from the physical-bodily tool. One attains a life of thinking, knowing that it is not bound to the human body, that it flows in the spiritual-soul. It is a great moment when one can say to oneself: You live in the spiritual-soul. You then realize that there really are higher spiritual insights that go beyond the life between birth and death. Something is created similar to the ability to remember, an ability to imagine, a life that we can call prenatal life. This prenatal life comes to the soul as an experience, as an inner experience. Immortality is no longer something to philosophize about. The powers that others use for philosophizing are used by the spiritual researcher to develop new abilities and to gain different experiences. The willpower can also be trained. The spiritual researcher takes his path of development into his own hands and tries to exercise self-discipline. By deciding to incorporate this or that habit, the will is cultivated. This realization will perhaps be taken up by many, as, for example, the realizations of a Copernicus or a Giordano Bruno were taken up when mankind still believed in the boundaries of the firmament. Those who become spiritual researchers themselves gain a new overview of the world and a deep knowledge of humanity. Not everyone can become a spiritual researcher. But in the spiritual worlds, everyone can penetrate due to today's world development. How can spiritual science enrich the life of education? A practical experiment has been conducted at the Waldorf School in Stuttgart. There is much talk today about the need for change in teaching. Nevertheless, it would be historically ungrateful and historically untrue to say that educational science is the furthest behind in scientific life. When I started to put my ideas into practice at the Waldorf School, it was my conviction that it was not education as a science that was primarily in need of reform, but that we needed a worldview that could directly inspire all art and thus also education, so that we would be able to apply the excellent principles of education that already exist everywhere. Spiritual science does not merely speak to the intellect; it encompasses the whole human being. Above all, a thorough knowledge of human nature is necessary. One can only penetrate into the real life of a human being through spiritual science. Through it, we acquire the ability to observe the human being from the stage of life when he changes his teeth. Only through spiritual science do we actually develop a more subtle power of observation. This teaches us to recognize how, in the first seven years of life, the human being is a purely imitative creature. An example: a five-year-old boy has stolen money from the drawer. The parents are deeply saddened. Unjustly so. The boy has just seen how the mother always takes money out of the drawer. Let us pick out something else. When the child reaches seven years of age and gets his second teeth, this also marks an organic, internal turning point. If one has learned to observe the spiritual and soul forces, one learns to recognize how the forces have reached a transition point here (Goethe's law of metamorphosis). In this year, human ideas begin to form in the child in such a way that they can be absorbed by the ability to remember. The forces break away from the organism, become soul-spiritual and appear as a separate power of imagination. These observations are as soundly based as chemical observations. They show that the abilities that the child develops through play up to the age of seven reappear later, but only in the twenties. In the meantime, they remain, so to speak, below the surface. In the meantime, the forces are used to gain life experience. From the age of seven, play becomes social play. Individual play only comes to life again in the twenties as the power of life experience. It is very nice when educational principles say that you have to draw out the dormant powers in a child. However, it is not the principles that are important, but knowing what can be developed in a child. After the seventh year – approximately – the instinct of imitation is joined by the instinct of authority. Anyone who knows human nature knows that from the change of teeth to sexual maturity, there is a predisposition for devotion to an external authority. The ninth year becomes the Rubicon again. The child breaks away from his surroundings in his inner consciousness and distinguishes himself from them. He distinguishes himself from his authority, but surrenders to it in love. These experiences must be taken into account in practical teaching. The first actions in primary school must be geared to the will, not to intellectuality. One penetrates to the conventional by way of art. Thus, writing is best developed out of drawing and painting. Other experiments have been made at Stuttgart. We have created a visible language. The movements of the larynx, as seen by supersensible vision, are translated into soul-inspired gymnastics (Eurythmy), in which every movement is the expression of a soul or spiritual process. The languages that a child is to learn should be presented to him as early as possible. In lively interaction with the teacher, we teach English and French to seven- and eight-year-olds, so that the child grows up with these languages. We teach languages because we know that this develops the whole being of the human being. Between the change of teeth and sexual maturity, one should not yet reckon with the child's power of judgment, but teach him every idea figuratively. If, for example, one wants to present the immortality of the human soul to the child conceptually, one can show the development of the butterfly. But it is essential that the teacher himself believes in the image presented. From the age of nine, the child begins to separate from the environment. Now we can appeal to his independent judgment. The spiritual science therefore reads the curriculum from the observed development of the child. It takes the world as it really is, and is therefore something eminently practical. Technical questions, such as determining the number of pupils per class, take a back seat. When the teacher has fulfilled his task, the necessary individual treatment of each pupil will not suffer, even with a large number of pupils. The pupils will individualize themselves. (The speaker made the aside that he had predicted the world war as early as the spring of 1914, when all cabinets believed that world peace was secured for a long time to come. We must approach practical life from an inner experience. The next generation must not be in the same condition as the generation that brought the misfortunes of the last years upon Europe. Anyone who has studied education from a spiritual science perspective knows that spiritual life must be placed on its own. This brings us to the social significance of the whole question. Today the world is more anti-social than ever. It is necessary to recognize that the spiritual life can only develop if it is placed under its own administration. Spiritual science recognizes that new movements, which have previously slumbered latently, are each pushing from the depths of humanity to the surface. Such phenomena are not explained by the law of cause and effect. For example, what is called democracy emerged for the first time in the 15th century and has since developed more and more. If we are sincere in our belief in democracy, we must separate from it everything that has nothing whatever to do with it. Only those matters which affect every adult in the same way can be administered democratically: public legal matters. But the spiritual life cannot be governed by the State. It must be placed under its own administration. Those who direct the spiritual life should also administer it. The same applies to economic life, which can only be judged by people who are experts in the field. This too must be removed from democratic administration. It must not be governed from a central office. Separate administrative organizations must be formed from the circles of consumers and producers. This threefold structure of the social state is not a parallel to Plato's tripartite division into the warrior class, the teacher class and the breadwinner class. Rather, each individual must be involved in all three. Our present chaos stems precisely from the fact that people stand side by side. In threefold socialism [social organism], however, they are to develop their powers organically. In the unitary state, the words equality, freedom, fraternity remain a lofty ideal. In the tripartite socialism [social organism], in which everyone is organically connected to all three links, they can be realized. Freedom will prevail in the spiritual life; the democratic administration of the legal life will bring equality to everyone; the self-reliant economic life will flourish in fraternity.

|